Passages: Beuys, Darboven, Kiefer, Richter

10.12.2006 - 02.25.2007

This exhibition highlights the work of four German artists who came to the attention of an international public during the second half of the 20th century: Joseph Beuys, Hanne Darboven, Anselm Kiefer, and Gerhard Richter. Although diverse in practice and subject, the works presented in Passages share an interest in the recording of time and of multiple routes through social, cultural, political, and artistic histories.

Affinities can be seen in the post-World War II practices of Beuys—exploring the profound despair and struggle faced by the nation, while encouraging a renewal of spirit—and of Darboven—chronicling time, evolving systems to mark the present and record what is past—with the painters Kiefer and Richter. Kiefer's canvases subvert the realism frequently suggested through the picture plane while maintaining cultural and historical references to national heritage and more specifically to the traditions of German painting. Richter's ongoing Atlas project gathers without hierarchy, amassing the raw materials of his artistic production.

Joseph Beuys's oeuvre retained aspects of Fluxus (a movement with which he was associated in the 1960s) such as performance and the privileging of social issues. However, Beuys's unique outlook evolved throughout his career, informed by diverse sources including German history, Shamanism, and Rudolf Steiner's anthroposophy, which postulates the ability of the human intellect to contact spiritual worlds. His awareness of alchemy led him to associate particular materials and forms with potential transformative qualities. Fusing art and artifact, Beuys assembled groups of objects, both found and created by him, in glass and metal cases similar to those found in anthropological museums.

From his first sculptures and drawings of the mid-1950s to his final environmental installation of 1985, Beuys created an intricate, medium-spanning body of art, organized around a rich tapestry of symbolic images and materials. One of Beuys’s most theatrical installations, Lightning with Stag in Its Glare (1958–85), articulates the German artist’s obsession with the earth, animals, and death. Completed in the year preceding the artist’s death, this monumental work comprises a number of theories and mythologies from which Beuys drew throughout his career, yet the meaning of this complex installation may ultimately be located within his definition of "social sculpture." He advocated, through his interactive and often politically charged practices, a change in thinking that develops out of personal understanding rather than technological advances. Intending to stimulate rather than represent, ideas through his work, Beuys hoped to rejuvenate—or illuminate—society with the fuel of creative thought.

Drawing from the natural sciences, philosophy, and the occult, Beuys interwove his oeuvre with recurring instances of felt, fat, copper, and iron; hares, stags, and bees; ritual healing and alchemical transformation; and an ever-developing utopian political philosophy. He hoped his gesamtkunstwerk—or total work of art—would obliterate all distinctions between art and life, leading to the realization that "everyone is an artist," and begin the process of healing the social wounds caused by excessive rationalism and divisive thought.

Key within Beuys's art practice was the production of editioned works, or multiples, of which this exhibition contains more than 550. Describing their "vehicle quality," he saw these works as the best means of widely disseminating his ideas. Because intuition played an important role in his thinking (as a corrective to reason), the multiples, like his other works, took on a host of abstract forms, appearing as sculptures, drawings, prints, photographs, films, audiotapes, and postcards. Shown individually or in dense clusters, they create endless linkages between themselves and the outside world, wrapping all of reality within Beuys's shamanistic worldview.

One of the most important German artists since the 1960s, Hanne Darboven has for decades produced handwritten "number constructions" as her primary mode of expression. For this German conceptualist, numbers not only represent an artificial, universal language, but also allow her to mark the passage of time. In 1973, Darboven started including texts by various authors, among them Heinrich Heine and Jean-Paul Sartre, in her work. By 1978, she was also incorporating visual documents, such as photographic images and assorted objects that she found, purchased, or received as gifts. These additional elements allowed her to explore specific and varied aspects of time and history—including an abstract version of biography—even as she remained faithful to her formal and conceptual approach.

As an artist totally focused on time and deeply committed to the theme of the century, Darboven naturally turned her attention to what that moment meant for her as an individual, and on a more universal level what one could say about art in the 20th century. In her commissioned installation for the Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin, Hommage à Picasso (2006), Darboven creates a daily record of the 1990s. Exactly 270 text panels filled with calendrical representations of the final decade of the 20th century cover the walls of the gallery. Other elements of the exhibition include a series of sculptures related to the work of Pablo Picasso, who is often thought to be the preeminent 20th-century artist, and a 120-part musical composition, Opus 60. This unusual work is simultaneously a portrait of the end of the 20th century and a self-portrait of Darboven as an artist, issues she investigates through the invocation of Picasso. Highlighting the limitations inherent in the Spaniard's late-career paintings, Darboven suggests that her conceptual approach is a more viable method for making art in the 21st century.

Born in Germany just months before the final European battle of World War II, Anselm Kiefer grew up witnessing the results of modern warfare and the division of his homeland. He also experienced the rebuilding of a fragmented nation and its struggle for renewal. Kiefer devoted himself to investigating the interwoven patterns of German mythology and history and the way they contributed to the rise of Fascism. He confronted these issues by violating aesthetic taboos and resurrecting sublimated icons. His paintings—immense landscapes and architectural interiors—invoke Germany's literary and political heritage. References abound to the Nibelungen and Wagner, Albert Speer's architecture, and Adolf Hitler.

During the 1980s, Anselm Kiefer became one of the foremost representatives of Neo-Expressionism, an approach characterized by violent, gestural brushwork and a return to the personal. His large-scale works, infused with references to both the German romantic tradition and his country's political heritage, combine a nearly monochromatic palette with mixed media, including the application of materials such as strips of lead, straw, plaster, seeds, ash, and soil. The result is an oeuvre whose monumental scale and rich interplay of textures heighten the solemnity and transcendental nature of its contents.

Beginning in the 1990s, after two decades of dealing almost exclusively with the horrors of the Holocaust and Germany's Nazi past, Kiefer began to explore a more universal set of themes, still based on religion, myth, and history, but now focusing on the spirituality of man and the internal workings of the mind. This new iconography, while still engaged with the weight of history, indicates that Kiefer now approaches his subject matter with admiration, even joy.

Born in Dresden in 1932, Gerhard Richter grew up under National Socialism and lived for another 16 years under East German Communism before moving to West Germany in 1961. Working with artists concentrated around Cologne and Dusseldorf in the 1960s, Richter found he shared a different view of Western consumer culture than did British and American Pop artists. With artists Sigmar Polke and Konrad Lueg, he briefly practiced a German form of Pop art they labeled "Capitalist Realism."

By 1962 Richter was painting works that, using a gray-scale palette, combined family snapshots and newspaper clippings. The artist has stated, "I mistrust the picture of reality conveyed to us by our senses, which is imperfect and circumscribed," and his insistence on the illusionistic nature of painting has led to a painterly practice that underscores the mediated experience of reality by incorporating imagery based on found and familiar photographs. Atlas, a vast compilation of such imagery begun in 1962 and expanded over the years, is testimony to the importance of photography within Richter's oeuvre. From the artist's perspective, photographs provide a pretext for a painting, injecting a measure of objectivity and eliminating the processes of apprehension and interpretation.

Atlas now consists of more than 700 panels of reproductions clipped from magazines and newspapers, amateur snapshots taken by or given to Richter, and working sketches. Each panel consists of a grid of images. The sources of Richter's paintings can be found in Atlas, but their arrangement is not rigidly chronological. Atlas is more of a repository of the imagery, thematically varied and open-ended, that catches Richter's eye: "In my picture atlas ... I can only get a handle on the flood of pictures by creating order, since there are no individual pictures at all anymore." While it records the passage of time, it also conflates time—in the fluidity of the chronology, the revisiting of subjects and themes, and the simultaneous proximity and distance to his artistic production. The grids appear to order the march of history—personal, social, and artistic—but also deny the tidiness and linearity of such an assertion.

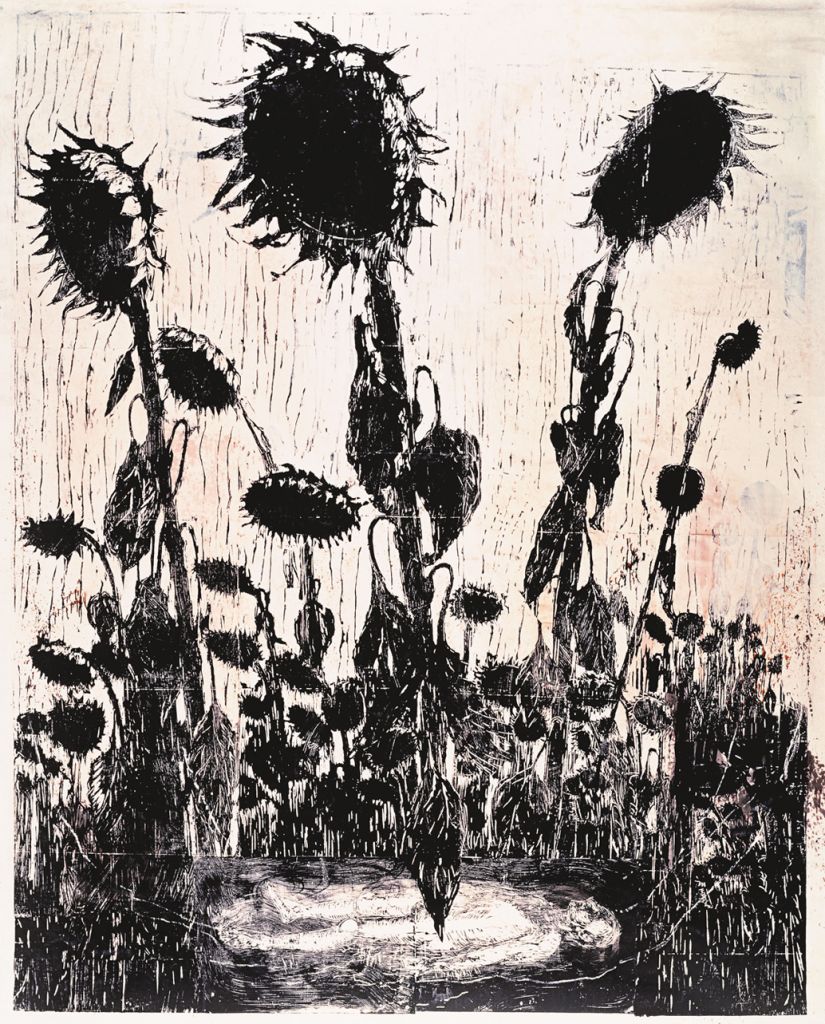

Anselm Kiefer

Sunflowers (Tournesols), 1996

Woodcut, shellac, and acrylic on canvas

442 x 360 x 4.5 cm

Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa