CUBISM AND THE AVANTGARDE

Cubism is among the most important artistic innovations to emerge in Paris in the first decades of the twentieth century. This revolutionary approach to painting—developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque between 1907 and 1914—challenged conventions of visual art and raised questions about the very nature of representation. Poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire is often credited with coining the term Cubism. He described it as “the art of depicting new wholes with formal elements borrowed not only from the reality of vision, but from that of conception.”

While Picasso and Braque exhibited their Cubist works in private salons and galleries, the wider Parisian public became familiar with the movement through the work of Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, and other painters of the so-called Puteaux group, named for the Paris suburb where many of them worked. Their Cubist canvases titillated and scandalized visitors to the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, an annual exhibition featuring progressive art excluded from more traditional academic shows. In the wake of widespread criticism provoked by the exhibition, Gleizes, with Metzinger, defended the movement to the public with a book that linked the Cubist aesthetic to modern innovations in science, mathematics, and philosophy.

Pablo Picasso was still living in Barcelona when the 1900 World’s Fair drew him to Paris for the first time. During the course of his two-month stay he immersed himself in art galleries as well as the bohemian cafés, night-clubs, and dance halls of Montmartre. Le Moulin de la Galette, his first Parisian painting, reflects his fascination with the lusty decadence and gaudy glamour of the famous dance hall, where bourgeois patrons and prostitutes rubbed shoulders. Picasso had yet to develop a unique style, but Le Moulin de la Galette is nonetheless a startling production for an artist who had just turned 19. In the painting, Picasso adopted the position of a sympathetic and intrigued observer of the spectacle of entertainment, suggesting its provocative appeal and artificiality. In richly vibrant colors, much brighter than any he had previously used, he captured the intoxicating scene as a dizzying blur of fashionable figures with expressionless faces.

In 1908, Georges Braque abandoned a bright Fauve palette and traditional perspective for the simplified faceted forms, flattened spatial planes, and muted colors of what came to be called Analytic Cubism. The hallmarks of this style, conceptualized as the breaking down or analysis of form and space, are seen in Piano and Mandola (Piano et mandore). Objects are still recognizable in the painting, but are fractured into multiple shards, as is the surrounding space with which they merge. The composition is set into motion as the eye moves from one faceted plane to the next, seeking to differentiate forms and to accommodate shifting sources of light and orientation. The naturalistic candle serves as a beacon of stability in an otherwise energized composition of exploding crystalline forms—from the disembodied black-and-white piano keys to the virtually disintegrated sheets of musi

Similar in style and composition to Georges Braque’s work of the period, Pablo Picasso’s Bottles and Glasses (Bouteilles et verres) exemplifies the moment in the development of Analytic Cubism when the degree of abstraction was so extreme that objects in the painting are almost unrecognizable. Picasso presents multiple views of each object in the still life, as if he had moved around it, and synthesizes them into a single compound image. The fragmentation of the image encourages a reading of abstract rather than representational form. The imagined volumes of the bottles and glasses dissolve into non-objective organizations of line, plane, light, and color. Interpenetrating facets of forms floating in a shallow, indeterminate space are defined and shaded by luminous and hatched brushstrokes. The chromatic sobriety characteristic of works by Picasso and Braque of this period corresponds with the cerebral nature of the issues they address.

In 1911, Marcel Duchamp was still adhering to the conventions of easel painting, formal composition, narrative structure, and individual inspiration. His formative years included participation in the artistic circle known as the Puteaux Group, which gathered at the home of his older brothers and fellow artists, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Jacques Villon, after 1910. During this period, Duchamp moved rapidly through a succession of Modernist styles before renouncing painting altogether in 1913 in favor of an art that privileged the intellectual over the optical. Prior to this conversion, which would radically alter the development of Western art, Duchamp frequently painted the members of his family. In Apropos of Little Sister (Àpropos de jeune soeur), the sitter is Magdeleine, Duchamp’s youngest sibling, who was 13 at the time. She is seated, reading a book by candlelight; her attenuated limbs and curving spine form a sinuous S-curve that reverberates in the loosely painted environment around her. The delicate, light colors are accentuated by the texture of the canvas itself and the angularity of forms suggests an awareness of Cubism. Painted at his family home in Rouen, it follows Duchamp’s early work which was influenced by Cezanne, the Fauves and Symbolists.

Albert Gleizes first began painting seriously while in the French military from 1901 to 1905, and again when serving during World War I. The sitter in Portrait of an Army Doctor (Portraitd'un médecin militaire) is Dr. Lambert, a surgeon attached to Gleizes’s regiment. Though neither the doctor’s identity nor his profession are clearly identified in the portrait, the colorful facets, circular areas, and intersecting diagonals are carefully arranged to delineate a figure. Some defining features are likewise emphasized, such as the doctor’s white clothing and dark mustache. The eight known surviving studies for this portrait are in the Guggenheim Museum’s collection, and together they demonstrate Gleizes’s gradual development toward the complex final composition. The resulting portrait presents a dignified and sober impression of the subject while reflecting Gleizes’s increasing interest in Cubist abstraction.

Juan Gris moved to Paris from his native Madrid in 1906, settling in the same building where Pablo Picasso lived. In Houses in Paris (Maisons à Paris), one of at least six canvases of Gris’s Montmartre neighborhood painted in 1911, the artist experimented with tropes he learned from Picasso and Georges Braque, while retaining his own sensibility and color palette. Creating severely flattened architectural spaces and rendering passages of shadow and light on their own plane, Gris applied a modern technique to the urban landscape—as Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger were doing in their paintings—while drawing on his work as a journal illustrator for the juxtaposition of shapes, strong tonal contrasts, and overall visual rhythm of the surface.

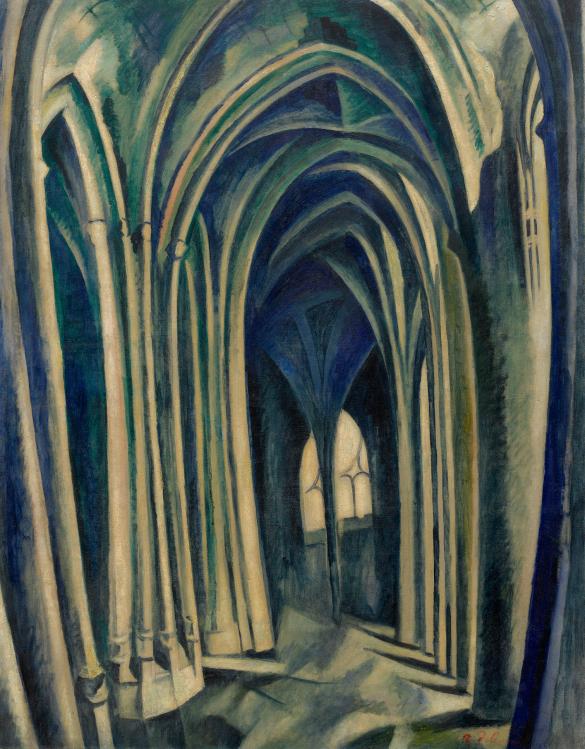

Robert Delaunay chose the view into the ambulatory of the Parisian Gothic church Saint-Séverin, located not far from his studio, as the subject of his first monumental series of paintings (1909–10). Described by the artist as “a period of transition from [Paul] Cézanne to Cubism,” the Saint-Séverin pictures are equally reminiscent of Cézanne’s fracturing and concentration of shifting light and Georges Braque’s early Cubist landscapes. Saint- Séverin No. 3 is the most muted of Delaunay’s series: beige, dark blue, and green are the only hues used throughout the composition and serve to chart the modulations of light streaming through the stained-glass windows. The elliptical movement of the piers, which bend toward the interior of the aisle, lend the painting an unsettling curving and bulging effect. Delaunay considered Saint-Séverin No. 3 the most representative of all the paintings in the series.