MODERNITY AND TRADITION

In the years leading up to and immediately following World War I, the visual language of Cubism was variously employed by artists interested in everything from exploring pure abstraction and modern science to infusing contemporary expressions with the spirituality of folk traditions. In the 1910s Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger, for instance, both explored the concept of fragmentation and simultaneity (the perception and passage of time) through their dynamic depictions of largely urban subjects. In the 1920s Delaunay was fascinated by new discoveries in optics and physics and developed a style that approached total abstraction. Apollinaire believed such work was similar to music in its independence from objective reality. He coined the word Orphism—referencing Orpheus, a lyre player from Greek mythology—to describe Delaunay’s endeavor.

Other artists such as the Russian-born Marc Chagall moved to Paris in 1910 and quickly began to absorb the latest styles. He combined the Cubist fragmentation of space that he saw in Delaunay’s paintings with colorful imagery inspired by elements of Russian and Jewish folklore. František Kupka likewise found formal inspiration in Cubism, Fauvism, and Delaunay’s work; yet as a follower of theosophy—a synthesis of philosophy, religion, and science—he also drew on ancient myths, color theory, and contemporary scientific developments as sources for his art. Constantin Brancusi—who came to Paris from his native Romania in 1904—rejected the theatrical, narrative impulse evident in much nineteenth-century sculpture in favor of radically simplified abstract forms and the unadorned presentation of wood, metal, and other materials. Though he never identified the precise sources and meanings of his work, several pieces in the exhibition may relate to supernatural figures from Romanian myths.

Robert Delaunay explored the developments of Cubist fragmentation in his series of paintings of the Eiffel Tower. Constructed in 1889 as a symbol of technological advancement, the Eiffel Tower captured the attention of painters and poets attempting to define the essence of modernity. In his own series on the subject, characteristic of his self-designated “destructive” phase, Delaunay presented the tower and surrounding buildings from various perspectives. In their limited palette and simple blocklike forms, Delaunay’s first treatments of the Eiffel Tower show the influence of Georges Braque and Paul Cézanne. The more dynamic representation of Eiffel Tower with Trees (Tour Eiffel aux arbres) signals a shift in the artist’s style. Delaunay showed the tower from several viewpoints at once, suggesting the movement of the eye through space and time and expressing a Simultanist vision.

The year 1912 marked the culmination of Analytic Cubism in the work of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque as well as the maturation of Fernand Léger’s idiosyncratic Cubist style, as manifested in his lively painting The Smokers (Les fumeurs). The curving, overlapping planes describe the corporeal forms of the painting’s subject while articulating an allover, rhythmically patterned surface. The resulting oscillation between volumetric body and dynamic space owes as much to Futurist aesthetics as to Analytic Cubism. With these thoroughly abstract images, Léger’s explorations of the Cubist idiom approached those of Robert Delaunay, whose later works like Circular Forms (Formes circulaires) neared complete detachment from empirical reality.

In his group of paintings Circular Forms (Formes circulaires, 1913 and 1930–31), Robert Delaunay did not seek to depict representational objects. Although the compositions were initially inspired by observations of planets and stars, he strived instead to present pure optical perception through investigations of color and light. The writer Guillaume Apollinaire coined the word Orphism—referencing Orpheus, a lyre player from Greek mythology—to describe Delaunay’s endeavor, which he believed was similar to music in its independence from descriptive reality. Departing from the limited palette of the early Cubism of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, Delaunay embraced bright colors and cast them in bands of concentric, fragmented circles, creating a kaleidoscopic effect. The color combinations in this work were inspired by the nineteenth-century French chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul’s theory of simultaneous contrast, which explores how juxtaposing different hues affects how each is perceived.

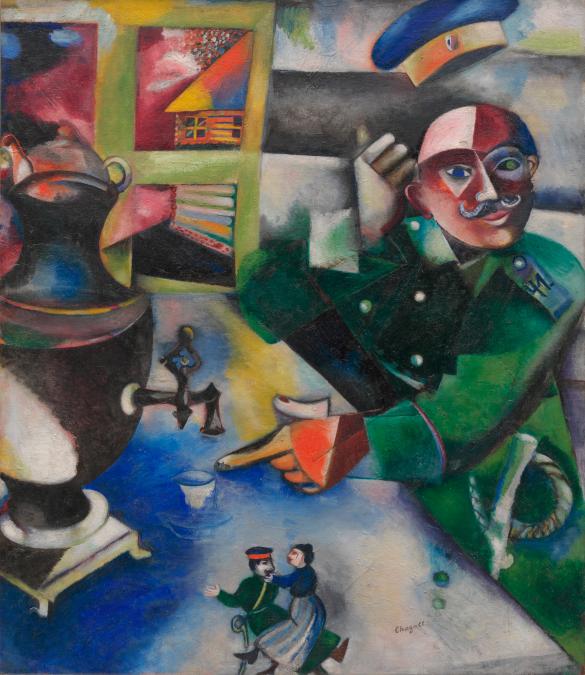

In 1910 Marc Chagall moved to Paris from Russia, where he encountered Fauvism and Cubism. Chagall’s paintings quickly began to reflect the latest styles; he merged Cubist fragmentation of space with colorful imagery inspired by his hometown and elements of Russian and Jewish folklore and legend. Years after Chagall painted The Soldier Drinks (Le soldat boit) he stated that it developed from his memory of tsarist soldiers who were billeted with families during the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese war. The enlisted man in the picture, with his right thumb pointing out the window and his left index finger pointing to the cup, figuratively mediates between dual worlds—interior versus exterior space, past and present, the imaginary and the real. In paintings such as this work, it is clear that the artist preferred the life of the mind, memory, and magical Symbolism over realistic representation.

When Piet Mondrian saw Cubist paintings by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso at a 1911 exhibition in Amsterdam, he was inspired to go to Paris. Tableau No. 2/Composition No. VII, painted a year after his arrival in 1912, exemplifies Mondrian’s regard for the new technique. With a procedure indebted to high Analytic Cubism, Mondrian broke down his motif—in this case a tree—into a scaffolding of interlocking black lines and planes of color; furthermore, his palette of close-valued ocher and gray tones resembles Cubist canvases. Yet Mondrian went beyond the Parisian Cubists’ degree of abstraction: his subjects are less recognizable, in part because he eschewed any suggestion of volume, and, unlike the Cubists, who rooted their compositions at the bottom of the canvas in order to depict a figure subject to gravity, Mondrian’s scaffolding fades at the painting’s edges.

Constantin Brancusi, a Romanian sculptor who settled in Paris after 1904, elicited from wood a tendency toward expressionism, and in doing so, developed a visual language uniquely his own. He counted among his friends Fernand Léger, Henri Matisse, Francis Picabia, and other modernists. Rejecting nineteenth-century sculptors’ emphasis on theatricality, detail, and narrative, Brancusi instead favored radical simplification and abbreviation. He sought to capture the essence of his subjects and render them visible with minimal formal means. The monumental oak King of Kings (Le roi des rois) was originally intended to stand in Brancusi's Temple of Meditation, a private sanctuary commissioned in 1933 by the Maharaja Yeshwant Rao Holkar of Indore. Although never realized, the temple—conceived as a windowless chamber (save for a ceiling aperture) with interior reflecting pool, frescoes of birds, and an underground entrance—would have embodied the concerns most essential to Brancusi's art: the idealization of aesthetic form; the integration of architecture, sculpture, and furniture; and the poetic evocation of spiritual thought.