SURREALISM AND ABSTRACTION

After the First World War, during which many avant-garde artists and poets died on the front lines, Paris once again became a center of cultural production. The adherents of Surrealism—a movement inaugurated with André Breton’s 1924 Surrealist manifesto—were also counted as part of the School of Paris. These writers and artists attempted to give form to or articulate notions of repressed desires, dream imagery, and the unconscious mind, drawing in part on the theories of Sigmund Freud. Some, like Max Ernst and Yves Tanguy, juxtaposed incongruous images and objects, while others, including Jean Arp and Joan Miró, experimented with automatism—drawing without a premeditated composition or subject as a means of bypassing consciousness.

Vasily Kandinsky, who made major strides in abstract painting while living in Germany and Russia in the 1910s and 1920s, settled in Paris in 1934. In his work from this period, Kandinsky synthesized motifs from other points in his career. Rhythmically arranged, freely playing forms similar to those from his earliest abstractions converge with the more geometric and biomorphic shapes he developed while teaching at the Bauhaus, a German arts and design school.Like many artists in Paris during the interwar period, Kandinsky was considered “degenerate” by the Nazis. With war looming again, artists who had once sought political, spiritual, and creative refuge in the French capital, including Fernand Léger and Tanguy, fled to the United States. The rise of Fascism and the city’s occupation ultimately ended the School of Paris.

In the early 1930s, Jean Arp developed the principle of the “constellation,” employing it in both his writings and artworks. As applied to poetry, the principle involved using a fixed group of words and focusing on the various ways of combining them, a technique that he compared to “the inconceivable multiplicity with which nature arranges a flower species in a field.” In making his Constellation reliefs, Arp would first identify a theme or set—for example, five white biomorphic shapes and two smaller black ones on a white ground—and then recombine these elements into different configurations. The Guggenheim Museum’s work is the last of three versions that Arp composed on this theme. His work, like Joan Miró's, engaged Surrealism at the level of process, for he used automatist strategies to get beyond the constrictions of rational thought. Jean Arp sought to devise an abstract art that would represent a truer indication of reality than representational art, because the way in which it would be created would echo the ways in which nature itself creates.

In 1927, Joan Miró painted a series of landscapes on his family’s farm in Montroig, Catalonia, where he had gone to recuperate from his bohemian life in Paris. In Landscape (The Hare) (Paysage [Le lièvre]), a line of multicolored dots swirls into a solar spiral, melding a stark orange sky with a bare expanse of burgundy earth below. The only life in this surreal terrain is a single whimsical hare. Miró later said that he was inspired to paint this canvas when he saw the animal dart across a field on a summer evening. This incident has been transformed to emphasize the unfolding of a heavenly event, as the hare with bulging eyes stares transfixed by a spiraling “comet.” By reimagining local landscape traditions in the avant-garde language of Surrealism, Miró attempted to reconcile modernism with his Catalan culture.

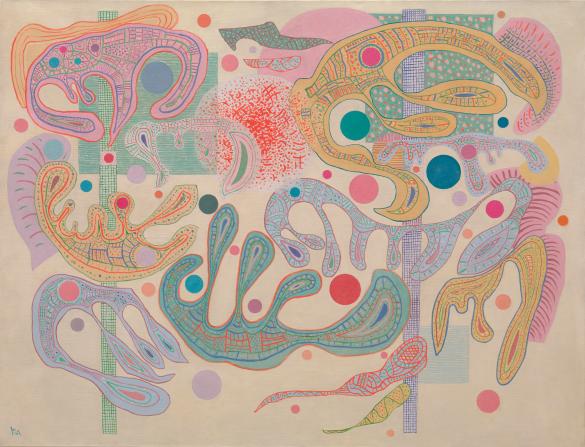

Vasily Kandinsky spent the last eleven years of his life in Neuilly-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris. He came to France in December 1933 as an émigré from Nazi Germany, following the close of the Berlin Bauhaus, where he had been a teacher. During this phase in his career, Kandinsky increasingly experimented with materials, creating imaginative works in which he combined sand with pigment. His intricate compositions from this period resemble miniscule worlds of living organisms, clearly informed by his contact with Surrealism, including the works of Jean Arp and Joan Miró, and his interest in the natural sciences, particularly embryology, zoology, and botany. Capricious Forms (Formes capricieuses) is a product of the artist at perhaps his most playful moment: interspersed with the clearly delineated circles and squares—the fundamental geometric shapes of his Bauhaus works—are floating and dancing curvilinear figures, all rendered in pastel shades. Several forms can be interpreted as stylized representations of embryo-shaped figures. The biological imagery may be read as the artist's optimistic vision for a not-too-distant future of rebirth and regeneration.

When Wifredo Lam arrived in Paris in 1938 he carried a letter of introduction to Pablo Picasso, with whom he had an immediate rapport. Soon after, he met many other leading artistic figures, including members of the Surrealist group. The Surrealists were fascinated by the mythologies of “primitive” people, and Lam, as a Cuban of African, Chinese, and European descent, was thought to have privileged access to that undifferentiated state of mind. In 1942 the artist returned to Cuba, where he developed a vocabulary of vegetal-animal forms inspired by Afro-Cuban and Haitian Santeria deities. In Zambezia, Zambezia, Lam depicts an iconic woman partly inspired by the femme-cheval (horse-headed woman) of the Santeria cult. He frequently depicted the transmogrification of body parts to suggest magical metamorphosis, which in this painting it is manifested in the testicle “chin” of the figure.

One year before Pablo Picasso painted the monumental still life Mandolin and Guitar (Mandoline et guitar), Cubism’s demise was announced during a Dada soiree in Paris by an audience member who shouted that “Picasso [was] dead on the field of battle”; the evening ended in a riot, which could be quelled only by the arrival of the police. Picasso’s subsequent series of nine vibrantly colored still lifes (1924–25), executed in a bold Synthetic Cubist style of overlapping and contiguous forms, discredited such a judgment and asserted the enduring value of the technique. But the artist was not simply resuscitating his previous discoveries in creating this new work; the rounded, organic shapes and saturated hues attest to his appreciation of contemporary developments in Surrealist painting, particularly as evinced in the work of André Masson and Joan Miró. The undulating lines, ornamental patterns, and broad chromatic elements of Mandolin and Guitar (Mandoline et guitar) foretell the emergence of a fully evolved sensual, biomorphic style in Picasso’s art.