Modern Painting and Sculpture

05.29.1999 - 05.14.2000

This installation, drawn from the permanent collections of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, highlights the changing course of the avant-garde over the first half of the 20th century. During that time, Europe experienced some of its most decisive historical events: the consequences of industrialization, the Russian Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, and two world wars. These dramatic circumstances had an impact on artistic practices as well. In the first decades, artists formed myriad associations and coalesced into movements, defending new ideals that broke more than purely aesthetic ground; such groups were known as the avant-garde.

It was the avant-garde that spearheaded the critical rebellion against tradition-laden society and questioned the great legacy of figurative Western art. The individual Modern work became increasingly self-referential, subject more to the laws of art than of nature. From then on, the source and justification of art was to be found in internal mental states rather than visible phenomena.

The early years of this century were marked by many of the revolutionary ideas that emerged prior to 1900. It was against this background that a number of artists began to explore a series of new approaches. Around 1907, Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso pioneered what came to be known as Cubism, one of the most influential and innovative art movements of the 20th century. Artists such as Picasso, Robert Delaunay, Lyonel Feininger, Albert Gleizes, and Juan Gris broke with traditional perspective and the illusory depiction of depth. Objects were shown simultaneously from a number of different points of view and fragmented into geometric planes. By contrast, the Expressionists focused their attention on the artist's inner world. Heinrich Campendonk, Vasily Kandinsky, Ernest Ludwig Kirchner, Oskar Kokoschka, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, and Egon Schiele used bright, unnatural colors and agitated brushstrokes in their search to explore subjective emotions. Kandinsky was later to shed virtually all vestiges of the natural world in his Improvisations, influenced as he was, like Paul Klee, by the example of music.

Two poles of abstraction flourished almost simultaneously for several decades, one promoting a rational aesthetic that emphasized principles of geometry and color theory, the other inspired by the world of the unconscious and advocating an art of pure imagination. Geometric abstraction arrived during World War I with the work of groups of artists from Germany and Russia. Abstraction's major proponents sought to eliminate all references to objective life from their compositions and eventually came to see "life through pure artistic feeling." At the same time, in Holland, a radical movement was developing around the journal De Stijl. Piet Mondrian, De Stijl's foremost exponent, advocated a universal aesthetic language combining geometric forms with predominantly primary colors, in addition to black and white. Functionality and technology loomed large in the ideas of the leading theorizers and artists from the Bauhaus, the German school of architecture and the applied arts, which had an enormous influence on the development of 20th-century architecture and art. Josef Albers, Kandinsky, Klee, and László Moholy-Nagy, among others, taught classes at the Bauhaus headquarters and consolidated the radical formal changes initiated by Cubism and Expressionism in a move toward total abstraction. In marked contrast, the Surrealists aimed to transfer the world of the unconscious onto the canvas. Influenced by Freudian psychoanalytic theory, they used techniques of psychic automatism as a means to access their own dreams, and to create idiosyncratic works that blend the rational and the irrational. The Surrealists revealed extraordinary imagination in their innovative, often child-like hallucinatory and oneiric images, which had an enormous impact on conventional society. Through the influence of Joan Miro's paintings and Jean Arp's sculptures and reliefs, biomorphic forms also became a primary element in much Surrealist work.

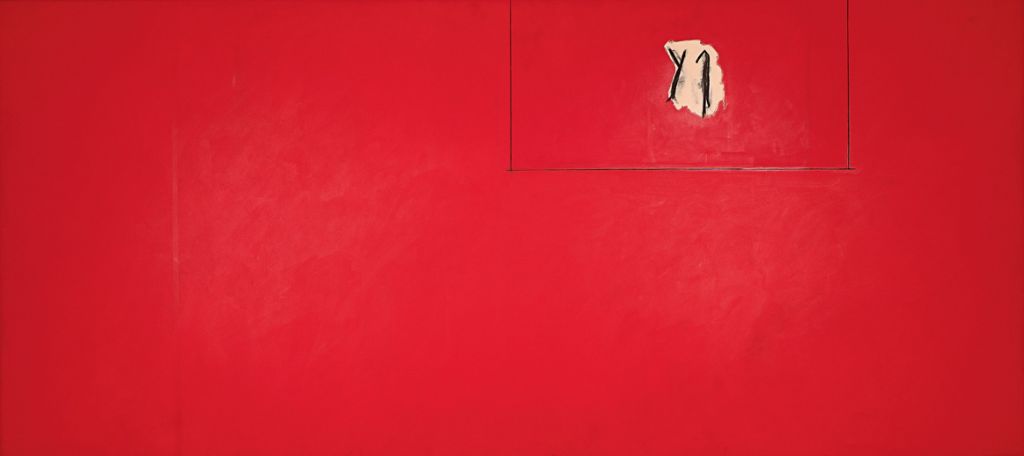

The rise of fascism and the advent of World War II caused many European artists to flee to the United States, particularly to New York. Among these refugees were former Bauhaus teachers, like Albers, and leading representatives of the Surrealists, who went on to exert a major influence on new generations of American artists, including the Abstract Expressionists. As a result, the United States inherited the legacy of Europe and became the new center of the art world in the west. Abstract Expressionism, often called Action Painting, was the first major artistic movement in postwar America. The foremost painters of the New York School sought to unite form and emotion, focusing the content of their paintings on introspective expression. Some, like William Baziotes, Willem de Kooning, Adolph Gottlieb, and Robert Motherwell, painted in a mode characterized by energetic brushwork. In addition to traditional brushes, they used novel procedures for applying paint (such as dripping and pouring paint directly from the can) thereby affirming the importance of the painted surface. With these methods, forms were often distributed imprecisely over the canvas, lending the works an air of spontaneity. Other artists, such as Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still, investigated the universal nature of human aspirations and spirituality through painting vast planes of color, prompting some critics to use the adjective "mystical" when describing their works.

Robert Motherwell

Phoenician Red Studio, 1977

Acrylic and charcoal on canvas

218.44 x 487.68 cm

Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa