Prologue

Gallery 205

Until lions have their own historians, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunters.

Chinua Achebe, Nigerian writer, interviewed in The Paris Review, 1994

"Until lions have their own historians, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunters."

Cyrus Kabiru: C-Stunners

Kenyan artist Cyrus Kabiru’s C-Stunners series of wearable eyewear sculptures blurs the boundaries between art, performance, fashion and design. The internationally acclaimed series extends to several media, ranging from sculptures to paintings and photographs that tell singular stories united by a shared message and meaning.

Each sculpture is created using items found in the artist’s surroundings – discarded objects such as screws, wire, spoons or crown corks, which Kabiru then assembles anew. Giving these objects a second chance, Kabiru harnesses the transformative power of transformation and reuse, advocating trash as a material in itself that can form the basis for creative work. At an abstract level, his eyewear sculptures speak of a different kind of transformation. The use of a pair of C-Stunners allows a new perspective on reality, reminding us how much a pair of glasses can narrow or focus one’s vision, and thus determine one’s view of the world. The C-Stunners series draws attention to the restrictive perspective from which Africa is usually looked at, tainted by prejudices that are far more difficult to put aside than a pair of glasses.

Ikiré Jones: The Untold Renaissance

This series of pocket handkerchiefs from fashion label Ikiré Jones’ The Untold Renaissance collection is intended as an homage to 18th century textiles and tapestries.

However, the brand’s head designer Walé Oyéjidé seeks to criticize the standard absence of dark-skinned people from historical textiles; using a sampling approach derived from hip-hop, Oyéjidé recreates individual works and narrates them from the perspective of Africans, whom he puts into this foreign context. Some of these new figures adopt new positions, others replace previous characters in their designated roles, weaving themselves seamlessly into the narrative. The stories told by these scenes are neither destroyed nor altered; they are simply infused with new dynamics. This oblique view of the past radically breaks the visual habits of the viewer, opening the space for new approaches and thought experiments on the absolutism of historical representations and the feeling of alienation, evoked by the character’s diverse skin colours.

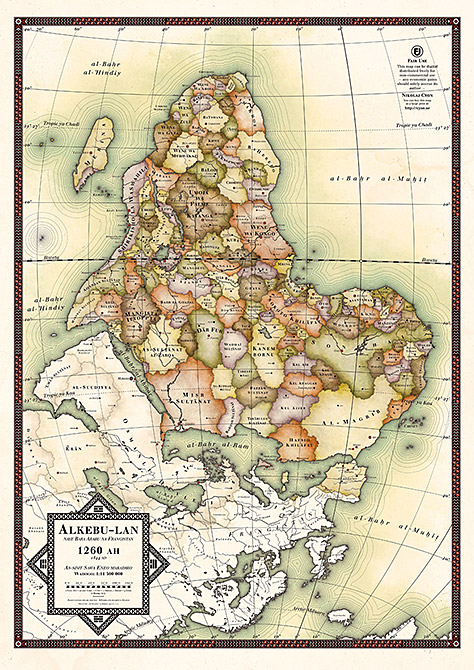

Nikolaj Cyon, Alkebu-Lan 1260 AH

What would the political map of Africa look like if the continent had never been colonized by Europeans?

Swedish artist Nikolaj Cyon seeks to answer this question in his map Alkebu-Lan 1260 AH – an old Arabic name for Africa, which translates to “land of the blacks”. Based on historical research, the map shows African countries, their boundaries, capitals and other important landmarks. There may be groups of people who identify with certain countries or names, and some of the towns have existed or still exist today. However, in Cyon’s map, the borders and the allocation of population groups to certain territories are largely fictitious; but the accuracy of the map’s content and the authenticity of its presentation deceive every European who grew up looking at a school atlas. Alkebu-Lan 1260 AH raises many questions: is it possible to transfer the European concepts of “nation”, “state”, “people” or “border” to the African reality? Are we doing a disservice to African political entities by trying to reduce them to European standards? Would Africa’s independent history be taken more seriously if it were expressed in a political geography more familiar to a European? Viewers have to find their own answers to these questions. Whatever the conclusions, one thing is clear: Cyon has literally turned the perception of Africa upside down.