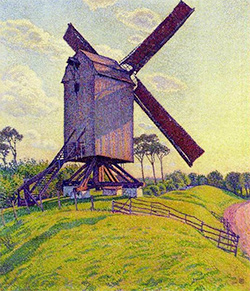

Kalf’s Mill in Knokke (Windmill in Flanders), 1894

Kalf’s Mill in Knokke (Windmill in Flanders) (Le Moulin du Kalf à Knokke [Moulin en Flandre]), 1894

Oil on canvas

80 x 70 cm

“A powerful play of complimentary colors activates the entire canvas. One feels an impression of joy, a song of colors.”[1]

In 1886, during a trip to Paris to view work by emerging artists, Théo Van Rysselberghe (Belgium, 1862–1926) was struck by Georges Seurat’s painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of Grande Jatte—1884 (Un dimanche après- midi sur l’île de la Grande Jatte, 1884-86), which he saw at the Society of Independent Artists. He was amazed by the use of color and the technique Seurat employed to apply paint. The work inspired Van Rysselberghe to adopt Seurat’s style: the division of color, known as

Neo-impressionism.[2] The Neo-Impressionist method is also called Pointillism.[3]

The Parisian fin-de-siècle was a time of political upheaval and cultural transformation. Interconnected movements in art, some looking to scientific theories, germinated alongside the insurrectionary philosophies and activities of incipient left-wing groups and an attendant backlash of conservatism. A new generation of artists emerged, known as the Neo-Impressionists. On the surface, their subject matter remained largely the same as that of their Impressionist predecessors: landscapes, the modern city, the activities of men and women at leisure, and so forth, but their technique differed considerably.[4]

These revolutionary painters looked to scientific notions of color and human perception to create optical effects in Pointillist canvases, and orchestrated complementary colors and mellifluous forms to render a unified whole. Utopian scenes that Neo-Impressionists frequently represented in their works married ideological content and technical theory. Yet even when not guided by overtly politicized objectives, the Neo-Impressionists’ shimmering interpretations of city, suburb, or countryside still depicted idealized places of harmony.[5]

Van Rysselberghe quickly embraced this new approach, but personalized it as well. His works remained more realistic in their conception, albeit capitalizing on Seurat’s technical innovations. He never abandoned the representation of three-dimensions or perspective, as Seurat had in the very flattened forms and planar interpretations of space in his compositions.[6]

Emulating Seurat’s method, van Rysselberghe applied minute dots of often complementary colors onto the picture plane. Because the dots are so close to each other, the viewer’s eye perceives them as single colors. Moreover, instead of mixing pigments on the canvas as before, Van Rysselberghe kept his small individual dashes of color separate, creating a brighter and more vivid image.[7]

When van Rysselberghe went to Paris with the poet Emile Verhaeren in 1886 he met Seurat, Paul Signac, and some of their followers.[8] Signac and van Rysselberghe became good friends and traveled and painted together in the early 1890s, producing a series of luminous Neo-Impressionist landscapes and seascapes, their surfaces composed of tightly knit brushstrokes.[9]

The Flemish scene Kalf’s Mill in Knokke (Windmill in Flanders) (Le Moulin du Kalf à Knokke [Moulin en Flandre]) (1894) was painted by van Rysselberghe at his Neo-Impressionist peak. A majestic windmill from Belgium’s countryside is depicted with his characteristic fractured brushstrokes of pure color. In the present work, he managed to capture the unique lighting on the scene’s different zones, visible in the various shades of grass and the chromatic richness of the wood.

After Seurat ‘s death, van Rysselberghe eventually eschewed the strict application of divided strokes of color in his portraits and landscapes. He began to use broader brushstrokes in a more realistic pictorial language. By 1903, his Neo-impressionist technique became more relaxed, and after 1910 he abandoned it altogether.

[1] Emile Verhaeren, L‘Art Moderne, 13 mars 1898; original French: “Un jeu puissant et varié de complémentaires mouvemente toute la toile. Une impression de joie, une chanson de couleurs s’entend.” In Ronald Feltkamp, Theo Van Rysselberghe, 1862-1926 (Editions Racine; 2003), 61.

[2] Vivien Greene, ed., Paris, Fin de Siècle: Signac, Redon, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Their Contemporaries exh. cat. (Bilbao: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2017), insert page number.

[3] “Pointillism” was a term coined by art critics in the late 1880s to make fun of the style some artists were using to create their artworks, but today it is used without the mocking connotation. The movement Seurat began with this technique is known as Neo-Impressionism.

[4] Vivien Greene, ed., Paris, Fin de Siècle: Signac, Redon, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Their Contemporaries exh. cat. (Bilbao: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2017), insert page number.

[5] Vivien Greene, ed., Paris, Fin de Siècle: Signac, Redon, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Their Contemporaries exh. cat. (Bilbao: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2017), insert page number.

[6] http://www.museothyssen.org/en/thyssen/ficha_obra/561

[8] http://www.wga.hu/bio_m/r/rysselbe/biograph.html

[9] https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/theo-van-rysselberghe-coastal-scene

Preguntas

Look closely at the work. Spend some time describing and analyzing all of its details. Where do you imagine this landscape is located?

Imagine that you can walk inside the painting. Where would you go? How does it feel to be there? What sounds and smells would you sense? What time of day is it? What season do you think it is? Why would you like to be there? Where do you imagine Théo van Rysselberghe was when he painted this canvas?

Have you ever been in a landscape setting similar to this one? What were you doing there? How do you think this painting is different from other landscape paintings you have seen before? To learn how to paint this work, van Rysselberghe traveled around Europe with his friend Paul Signac. They liked to work outdoors, at first painting directly from nature, and then working in the studio. What are the advantages and disadvantages of working indoors (in a studio) or outdoors (in nature)? Which would you prefer as an artist, and why?

Now observe the painting again. How do you think van Rysselberghe painted Kalf’s Mill in Knokke? What special technique was he using? How would you describe the brushstrokes? If you could use a magnify glass to look at the surface, what would you see?